Hollywood Samizdat

I wrote a book. It is very good and you will like it.

I recently heard a story about the director Joe Pytka and how he pissed on a PA.

He whipped out his cock and peed on the poor kid.

And no, this isn’t in the book. I wasn’t there, and I never actually met this director. But he (allegedly) pissed on one of his employees.

Stories like this are what I call Hollywood Samizdat—the stories that get passed around on film sets. They’re tales of nightmare tantrums of actors. Or bad behavior by producers and directors. Or things that just went seriously wrong—usually as the result of someone’s incompetence.

Everyone who’s worked with Joe Pytka has a story, and Pytka stories are their own sub-genre of Hollywood Samizdat.

I hear Pytka is retired now, but he was (and is) an absolute legend. Joe was never a household name, but he was well known in The Industry. He was mostly a commercial and music video guy, but he did a few films. He was known for his directing and cinematography chops—this guy was good. Actually, he might be the GOAT.

Any commercial or music video of note from the 1980s thru the early 2000s was directed by Joe. All the Michael Jordan stuff, all the Tiger Woods stuff, Bartels & James wine coolers, Cindy Crawford drinking a Pepsi, the Budweiser Clydesdales. He did it all.

But it was his abusive conduct that made him a legend. His tantrums were epic—and the stories about them are almost mythical.

This guy would scream—berating grown men to the point of tears. He would hit. And punch. He would throw heavy objects at people’s heads. In a fit of rage (and he was always raging) he threw a Panavision camera body—a camera with a million dollar replacement value—off a cliff. He even (allegedly) broke someone’s arm.

There are so many stories about this guy. And they’re so crazy that people can’t help but tell them. Like the worn out hand-typed manuscript of a Soviet dissident, they get passed around and get better with every telling. So it’s hard to know what’s real and what’s hyperbole.

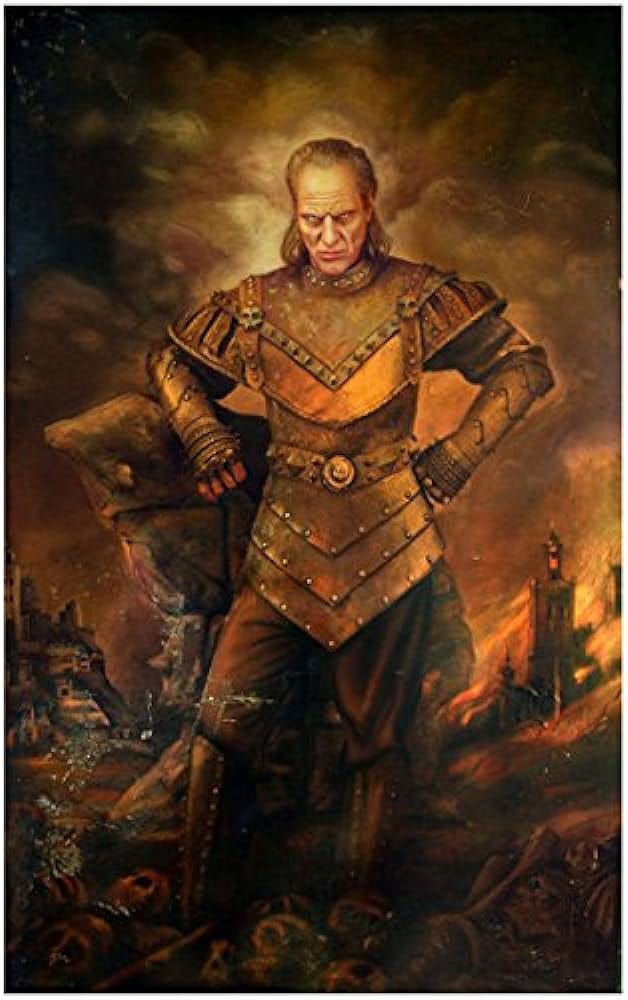

He was immortalized as the portrait of Vigo the Carpathian in Ghostbusters 2. The story I heard was an artist was hired to paint a portrait of a fictional historic villain who would later come to life and terrorize the Ghostbusters.

The artist asked what this villain should look like.

The production designer said, “Just paint the most horrible person you can think of.”

So the artist painted a portrait of Joe Pytka.

My favorite Pytka story is about the time he got busted for cocaine possession. The judge ordered him to do community service in the form of a public service announcement (PSA) about the dangers of drug use.

So he goes home. And in his kitchen, along with a stuntman/actor buddy, shoots the famous “This is Your Brain on Drugs” spot. It was the most popular PSA of all time.

A Twitter friend who worked for Pytka told me the pissing story. I’ll let my friend identify himself, but here’s the background:

Pytka loved sports. And on shoot days he’d play basket ball or throw a football or something in between setups. I heard another story (from another friend) that he always rolled with a portable basketball standard, and the PA who drove the production truck would wear tear off warmup pants just in case the boss wanted to play one on one in the basecamp. I’m not sure it that this story is true, but it’s a good story so I’m rolling with it.

More background:

A production needs a lot of trucks and trailers and assorted vehicles. When shooting on location (that is, not on a stage) they need a place to stage everything, so they get what’s called a “basecamp”. Usually this is a large open air parking lot.

Got it?

Good.

Here’s the story:

One day my Twitter friend is working as a PA for Joe. They’re in some basecamp and killing time inbetween setups. The boss is playing catch with the PAs. They’re tossing around a football and one of the PAs starts showing up Pytka. Maybe he intercepted a pass. I forget the details, but the point is Pytka got angry. And you don’t anger Joe Pytka.

Pytka didn’t like being shown up by the PA. So he picked up the PA and threw the kid on the ground. Just body slammed him. Then, to drive the point home (and assert his dominance) he whipped out his dick and pissed on him.

This was a junior employee.

And the director assaulted him (allegedly).

And then the director pissed on him (allegedly).

In public.

In a parking lot in Los Angeles.

In front of the cast and crew and everyone else who was watching.

And there was nothing the kid could do. Because directors can (and will) do anything.

Again, I wasn’t there. I didn’t see this happen. And I have no idea if it’s true.

But I tend to believe this story.

Because this is the type of shit that happens on set. And this is the type of story film workers share with each other.

This is Hollywood Samizdat.

I wrote a book. It’s called Hollywood Samizdat: Notes From Below the Line.

It’s a good book. And I think you’ll like it.

But it’s not about Hollywood. It’s not a celebrity tell-all. It’s not a manifesto about taking the Film Industry back from The Libs. And it’s certainly not a book of film critique (because there is nothing more cringe than film critique).

It’s not a book about Hollywood. It’s a book about me.

But then again it IS about Hollywood. Because I can’t write about myself without writing about The Business. I’ve been there too long. Almost a quarter century now.

I spent too many hours. Too many days. Too many years. It’s in me. I’m intertwined with The Business. And as much as I want to shake loose and run—as much as I want to leave—I can’t seem to break free.

And I have stories. So many stories…

In The Business, we don’t call these stories “Hollywood Samizdat”.

As far as I know I coined the term. But it seems appropriate. Because we’re not supposed to circulate these stories. Just like Soviet dissidents weren’t supposed to circulate theirs.

There’s a unwritten and unsaid code of silence: what happens on set stays on set.

We’re not supposed to talk about it.

We’re supposed to keep our mouths shut.

But film work can be tedious. And there’s a lot of downtime on set. So we tell stories to pass the hours.

We tell these stories in confidence. There’s an understanding that the story should not be passed around, and it’s certainly not for pubic consumption.

We don’t tell the stories in public because we’d never get hired again. The good stories involve the people in power. The actors, directors, etc. And they’re not going to work with anyone who violates the Code of Silence.

So it’s career suicide to violate it—first and foremost because nobody wants to work with a gossip.

So we only tell these stories to each other. And mostly it’s due to The Code.

But there’s another reason we only tell these things to each other. It’s because nobody outside the industry understands.

They don’t understand why the urine soaked kid didn’t jump up and kick the director’s ass. They don’t understand why there wasn’t a lawsuit. They don’t understand that this is Hollywood. That this is a different world. And we do things differently here. And the normal rules don’t apply.

It’s a world too strange for most people to comprehend. And the strange things that happen on film sets can only happen on film sets. So people who have never been on a film set have no frame of reference.

And trying to explain things to them is futile.

I know because I’ve tried.

You can only tell these stories to someone who’s been there.

Because only someone who’s been there will understand.

I keep moving further and further away from The Industry. Aside from physically moving (I left LA over a decade ago), I’ve been moving away professionally as well.

I’m not completely out, but I’m close.

But the further away I move, the stranger it all seems. And like people outside the industry—like the civilians—I no longer understand these stories.

All the stories in the book are true (sadly). I changed some details to obscure my identity, and to protect the innocent (as well as the guilty). But the gist of it is true.

These are things that happened to me. And I find myself trying to find meaning in it.

It all made sense at the time, but now it doesn’t.

It’s become a puzzle. Perhaps it’s because I’m losing my own frame of reference.

So I search for morals. I search for meaning. Even though I know there isn’t any moral or lesson or meaning. It’s just shit that happened.

Because sometimes shit just happens.

Maybe I needed some sort of closure. I needed to file this stuff away. Because it keeps tripping me up. And I need to move on.

So I started writing. I wrote to sort my thoughts.

This book is me telling my story to myself. The secret stories. My own personal samizdat.

While most of these stories are related to my life in The Industry, some are not. Some of the stories explore other things and go other places.

The common thread is this: these are the stories I couldn’t tell to myself. Not out of shame or embarrassment or career preservation—but because I didn’t know how to tell them.

If you’ve been following me on social media you might recognize some of these stories. Some of them started at Twitter posts. Then I’d rewrite them for Substack. Finally I rewrote and expanded them for the book.

But there’s new stuff too—stories you haven’t seen yet.

Some of it was hard to write. There’s a place inside me. It’s a place free from bullshit. It’s hard to get to. And it’s a painful place to be. I don’t like to go there. I don’t like to be there.

But when I do go there—when I find that place—things flow. It’s like the words just fall out of me.

When I’m in that place it doesn’t feel like writing. It feels more like typing. Like I was transcribing something that was already written. Like it was always there—I just had to find it.

But I didn’t do it myself.

I had some help—mainly from my remarkable editor Michael Lacoy. He was constantly pushing me to be better. He wasn’t afraid to be brutally honest and tell me what I needed to hear, instead of what I wanted to hear. And he gave me a masterclass in writing. Working with Michael was the best part of the book writing process and I’m eternally grateful.

I’d also like to thank Jonathan Keeperman and Passage Press, who decided to take a chance on a messy unconventional manuscript written by a high school dropout. As such, I’m immensely indebted to Lomez and the team at Passage.

There are others as well. You know who your are. Thank you for your inspiration and encouragement. I hope I can repay it someday.

Back to Joe Pytka…

As I mentioned I never met the guy. But my wife used to work for him.

Joe never took breaks. Also, he never did any prep. He just shot. So she was on set with him 5 days a week.

And no, she didn’t get pissed on. Or got her arm broken. Or got stuffed into a trash can (yes, he’d do that). She didn’t even get yelled at.

I have a theory as to why.

Joe Pytka is a tall man. And she’s petit—like 5’ 2”.

So I don’t think he ever saw her.

When shit went wrong he’d abuse the first person he saw. But he never saw her. He never looked down.

Every time she went to work for Pytka I braced myself for the day when she took the brunt of his anger and come home in tears. Victims of his abuse would often quit the business. They’d walk away and never come back. He was notorious for that.

Aside from being abusive, he was also generous. But the tales of his generosity don’t get passed around like the abuse stories. One story I heard involved pizza and beer. He always made sure the crew had hot pizza and beer at wrap.

One time they were shooting in some godforsaken remote location many hours from civilization. Joe paid tens of thousands of dollars for a helicopter to bring in hot pizza and cold beer for the crew. That was a very nice thing to do.

He also paid his crew well. Better than anyone else. When my wife worked for Joe she was probably the best paid assistant stylist in Los Angeles. And that’s why she kept working for him even though there was a risk of, say, getting screamed at and peed on.

But again, it never happened. Joe never went after her. All because he never bothered to look down.

But my wife (as well as others who did long stints with Joe) has another explanation. To avoid the wrath of Joe Pytka all you had to do was be really good at your job.

He demanded excellence and had zero tolerance for complacency. So as long as you were buttoned up—as long as you were at the top of your game—you had nothing to worry about. Simple.

After Pytka, my wife got on a popular TV show. Then she became the costumer for a biggish actress. Then I got her pregnant and she became a full-time mom. She never looked back. She just moved on.

She worked for him around the time the pissing story took place. I told her the story and asked if she remembered that particular incident.

She paused and thought for bit and said, “It sounds familiar. But things like that happened every day and it all blurs together.”

It happened every day.

And it’s all blurs together.

I know this is true. Because it’s all a blur for me as well.

It takes time and effort to sort it out.

Hollywood Samizdat: Notes From Below the Line is now available to pre-order. Click here to purchase.

In Hawaii it wasn’t so bad because they were terrified of our teamsters who came from the local criminal underground and had a reputation for murder and setting things on fire. So many people are related here that it’s really risky to show up from somewhere else and start stepping on random toes. We basically had to train the Californians to live aloha, which has nothing to do with being nice and obedient but is actually a code of conduct that keeps this place from turning into a cannibal holocaust. Looking forward to the book!

Lol the pissing thing sounds like a flex. Like how LBJ would talk to reporters in the bathroom while he was shitting with the stall door open just because he could and what were they going to do about it?

As much of an abusive asshole as Pytka sounds like, I'm sure he's also a guy that if someone sees his name on your resume and the time worked is more than a week, they're like "Get this guy." Trial by fire has a way of making people decide how serious they are about the craft and I'm sure his antics weeded out a lot of people that would have been liabilities on set.

Looking forward to the book!